UPDATED October 25th, 2019 — this is a dispatch from my cycle tour of Ukraine and surroundings this past Summer with my partner Nastia, an open project on an Autumn/Winter hiatus — check out the project page more information, and sign up for my newsletter if you would like to be notified when it resumes 🙂

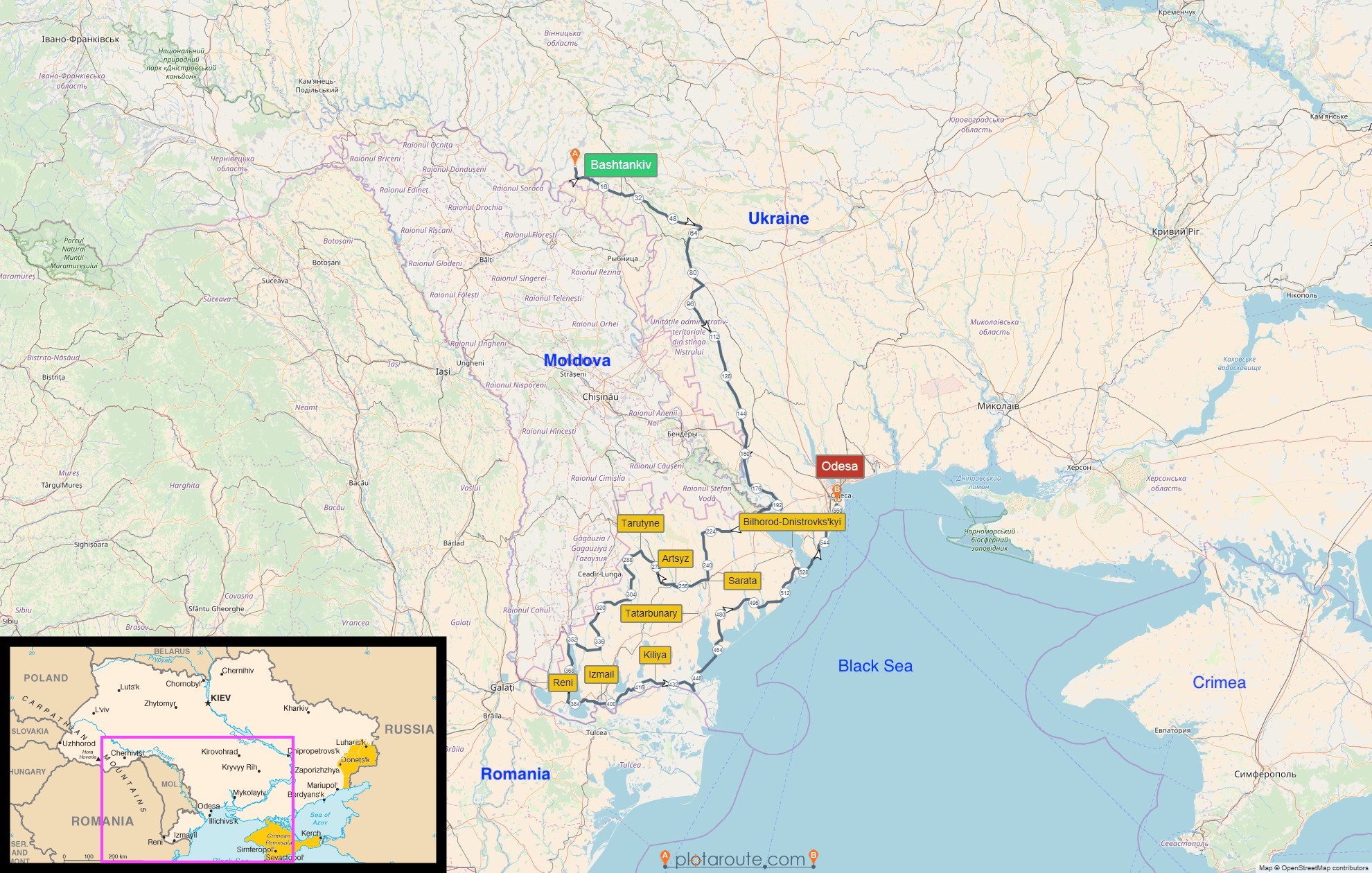

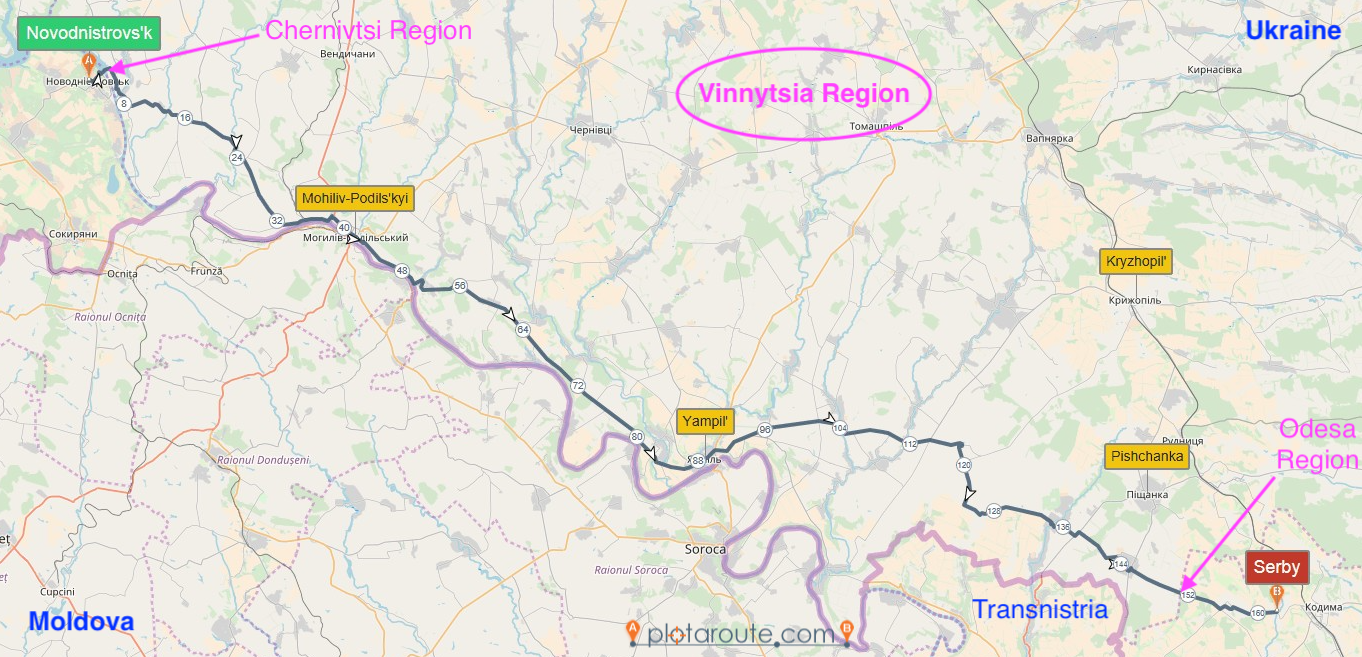

After four days in the region of Vinnytsia, we spent four weeks in Odesa — we took our time riding the 900 kilometers or so from the administrative border to the city of Odesa proper, following the region’s perimeter along Transnistria, Moldova, the Danube River, and the Black Sea.

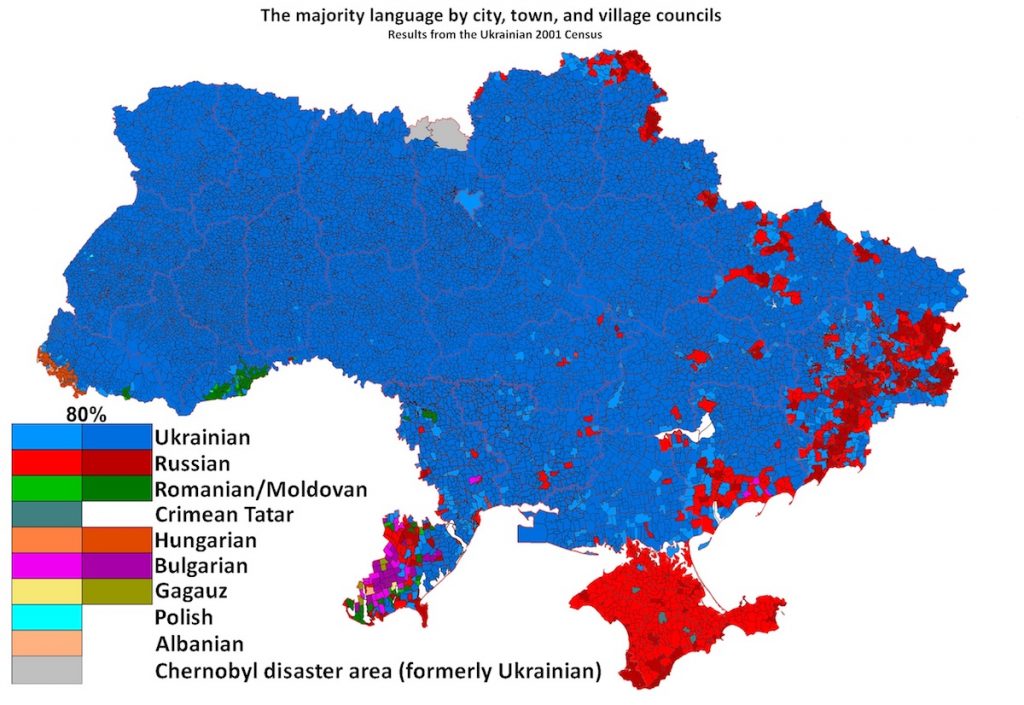

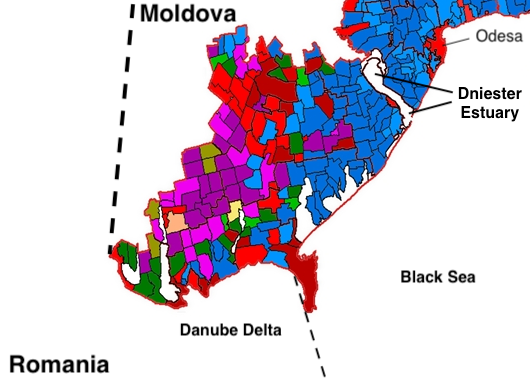

That was my second time in the region — my first time in Odesa was also my first time in Ukraine, two Summers ago during my 2017 cycle tour. Upon arriving in the city of Odesa on that trip, people who could speak English confirmed to me that they were talking to each other in Russian, and implied that that might have been the case in most places where i’d just traveled in the countryside as well. Confused about what language was Ukrainian, i eventually searched online for “languages

There’s a lot in there that

I left Odesa in 2017 without experiencing and utterly unaware of that variation, and had been wanting to explore it a bit further ever since seeing the demographic map. It was built on data from a 2001 census though — would that diversity still be there? — how did that happen? I searched again for “languages spoken in Odesa” and such, and the same map (or coarser variations based on not much more recent data from less comprehensive surveys) kept coming up.

Getting there without going through Moldova would be a significant detour in space and time from our ambition to reach the East of Ukraine. But if that linguistic kaleidoscope still existed, Nastia and i wanted to experience what some of it looked and sounded like in real life — we agreed that taking the southwestward detour was worth the risk not to find anything, as well as the delay to eventually getting across the Dnieper River.

Here is a snapshot (or nine) of what developed 🙂

Some languages used in Odesa

” ‘I’ve got to paint,’ he repeated. “

W. Somerset Maugham, The Moon and Sixpence

This essay is the third one in a series on each of the administrative regions of Ukraine that Nastia and i have visited on our tour — if you missed the bus stops of Chernivtsi or the location markers of Vinnytsia, feel invited to check them out — the three pieces are independent, but reading them in order might help you understand my process better.

At first,

I agree that shooting videos of people speaking in their languages and editing a mini-documentary of that would probably have made more sense. In hindsight, that might have also been less complicated than

Nastia did shoot some videos, and i’ll let you know if she eventually does something with them. Meanwhile, i’ll once again tell this brief story in a few photos — one per language (broadly construed) and, as it turns out, also one per district, in the order they were taken.

If you like to follow stories that unfold across a geographical area on a map, i hope these two will help — the left one highlights the administrative region of Odesa, and the right one names its districts (click to enlarge).

images courtesy of TUBS and AndrewRT (CC BY-SA 4.0)

UKRAINIAN

My initial strategy when we crossed the Dniester into the Bilhorod-Dnistrovs’kyi district was to stop in each village, look for people with a few minutes to spare, and explain to them what we were doing.

Consistent with what to statistically expect from the language distribution map, Sasha and his family spoke Ukrainian — “As your first language?” — “Yes” — “And do you know anybody here whose mother tongue is not Ukrainian or Russian?” — “Not really, we’re all Ukrainian around here.”

They did confirm that there were people from various nationalities in the

TAJIK

We kept riding, and we kept asking — people kept turning out Ukrainian, and continued to announce the region’s diversity further along — “There are people from 113 different nationalities in Odesa,” someone told me sounding as if they’d heard that precise number on last week’s Friday documentary on TV. Even if those figures were exaggerated by a factor of several, and took into account people carrying a foreign passport in their pockets on the streets of Odesa, we should be in for a treat.

I eventually heard about an Armenian, and the woman who knew him gave me directions to his home — “go back, turn left onto that street, then ride all the way up, it’s one, two, three, four — the fifth house on the left,” she said raising a finger to match each number uttered. Following directions and counting houses in a village as an outsider is a challenge i’d face a few more times — it wouldn’t get easier — is this where i’m supposed to start counting? — is that the next house already, or is it just a barn, or their Summer kitchen, or the next generation’s abode, but within the same property, so it doesn’t count?

After a couple of false positives, i finally found it — “hello, are you Alik,” i asked — “Yes,” he answered inquisitively, closing the gate behind him as he walked outside towards me — “I was told you are from Armenia?” — “Tajikistan — who are you?”

I would also have been suspicious.

It was soon clear enough that i was merely a curious nobody — “OK — would you like to have something to drink?” — “Oh, thank you so much for the invitation, but it’s a little early for that, and i still have a lot to ride today” — he interjected seemingly insulted, “I meant tea, or coffee!”

Tajiks are not quite a national minority in Ukraine — especially not in the sense that you’d find Tajik communities here — you most certainly won’t. Like the occasional Belarussians, Kazakhs, Russians, and emigrants from other former Soviet republics you’ll see sprinkled across Ukraine, Alik arrived before 1991, and then stayed — his wife passed away, his children left home, and he now lives alone.

He asked me to call him now and then, and i said i would — i want to — i haven’t yet.

While i had coffee with Alik, who also offered me lunch (a chickpea soup with a piece of chicken — the only one he’d cooked that day, as i inferred from the absence of another one on his plate), Nastia gathered intelligence outside the mahazyn in the village center, where she’d stopped to wait for me — someone there knew the region very well, and left our map with glittering notes on where to find who.

GAGAUZ

This annotated map didn’t say anything about the district of Tarutyne, which was out of the way, and Nastia wanted to skip. The idea of how i might eventually put this together was gradually taking shape, and leaving a district out gave me spiritual unease — i guess we didn’t have to stop in every village, but i still wanted to meet people in each of the nine districts comprising Budzhak — we swang by Tarutyne.

We had just spent half the afternoon talking to the head of the village where we’d stopped for lunch and were looking for water to refill our bottles on our way out when we finally met not only one, but three Gagauzes who agreed to be on the camera — they even sang to us!

That was also the day Nastia realized that some people in Ukraine don’t speak or understand Ukrainian at all — a couple of days later, we would learn that a few of them can barely deliver in Russian.

Nobody we met knew where the Gagauzes came from or how they got there — according to Wikipedia, a Bulgarian historian at the beginning of the 20th century counted 19 different theories, a number that increased to 21 by another historian a few decades later. Their language belongs to the same branch as Turkish and, if i understood it correctly, they’re somewhat mutually intelligible.

BULGARIAN

We went back to the leads on our annotated map — ethnic Bulgarians were who we met the most, which was consistent with what to expect based on that, as well as the language map in the preamble. Given how i eventually chose to put this together, i had to pick one of them.

Besides what i thought that it would be super cool to select a unique language from each district, i also believe it is valuable to include F’odor on this brief essay for a second reason — he explicitly wants his children to learn Ukrainian, and believes that promoting the language over Russian in the public sphere is a necessary step to establish a Ukrainian national identity.

While we met many people indifferent to the national government’s language policy, finding someone who defended it amidst so many who opposed it drew my attention.

ALBANIAN

When the Bulgarians came to Bessarabia, a few Albanians who had settled in eastern Bulgaria sometime before tagged along [1]. Their descendants in Odesa concentrate in Karakurt. We arrived there close to dark hoping not only to meet some of

We learned the next day that the event had been the inauguration of a monument to Albanian hero Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg — the family who eventually hosted us wondered why on Earth the head of the village hadn’t invited us to join her! I can’t complain — as it is usually the case, it worked out great.

The highlight of what i learned on those one-and-a-half days was that, in a vast country like Ukraine, different people might look up to different historical figures — along our tour of Bolhrad, i counted four monuments to Ivan Inzov (including the mausoleum where his remains rest), a General of the Infantry in the Russian Empire in the early 1800s, and one statue of Taras Shevchenko, the celebrated poet and polymath whose literary legacy is considered the foundation of modern Ukrainian language — the monument was only recently inaugurated, to replace a fallen Lenin.

MOLDOVAN

Moldovans were the second most prevalent minority throughout the region after the Bulgarians. It was particularly unsurprising to find them in the Reni district, which is wedged between Moldova and Romania — even back in 2017, though still oblivious to how colorful a demographic map of Ukraine might look like, i was already aware that languages reliably leak across political borders — my rudimentary Romanian was useful in asking for water or directions a couple of times along the Danube.

What was unexpected in our encounter with Oleksandr was his friend Ihor, from L’viv. I’ll do my best to be fair to the guy — Ihor was nice to us — he actually came to Nastia and i, and invited us to join him and Oleksandr at their table — he offered us something to eat, gave us his phone number, and asked us to look him up in L’viv when we came back.

That didn’t override our annoyance when he kept taking over, whenever we asked Oleksandr a question, to say things like, “He speaks Romanian — did you know the Constitutional Court of Moldova ruled that Moldovan and Romanian are the same language?” — what is that even supposed to mean? Ihor expected us to know Stepan Bandera‘s birthdate and patronymic — is that what Ukrainian nationalism is coming down to? — was he just jealous because we were far more interested in his Moldovan friend?

I regret not confronting him then and there with these questions — i wanted to write about Oleksandr, and have next to nothing about him in my memory or notes now. Oleksandr, in turn, displayed generous amounts of patience with his friend.

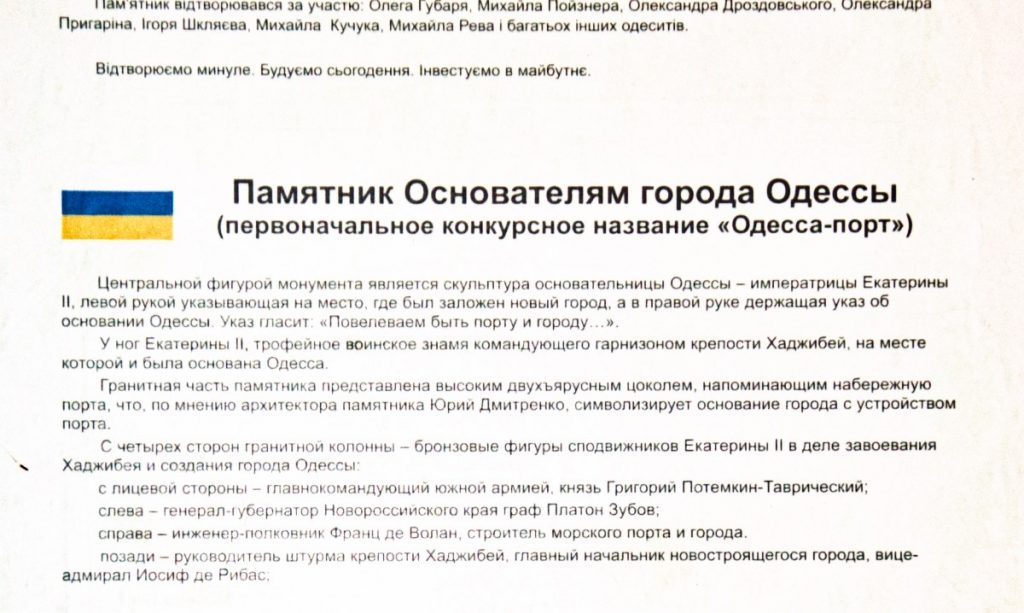

RUSSIAN

A guy behind me interrupted my process, wondering what i was doing while i crouched, kneeled, leaned, and laid awkwardly on the sidewalk, trying to compose an overlay of a monument and a trash can — i felt embarrassed, but the experiment was disastrous in the artistic dimension as well, so my intention could hardly be gleaned from the previews i showed him — i told him i had to join my wife, who was buying pastries across the road, and he let me go easily.

He caught up with me a little later that day, and i asked him if he knew where was the post office, where he gladly walked me — we started talking — “may i ask what is your nationality?”

After a brief pause, “I’m Ukrainian,” he said, still a bit hesitantly. “I was born in Russia — well, modern-day Russia — I’m Soviet.”

“Soviet!?

“Soviet. You asked what’s my nationality — that’s what i was taught — almost anybody about my age or older will give you a similar answer — that’s what we grew up with, it was all one country.”

He didn’t sound nostalgic or resentful — i was probably startled by his answer more because i could clearly understand it — we were having this conversation in our mutual English rather than my broken Ukrainian or Nastia’s truncated mediation.

Dmitriy’s attitude resonated with what i’d intellectually gotten from some people we’d talked to along our way across Ukraine, not just in Odesa. Writing about this episode makes me wonder how resentment or nostalgia develop — i didn’t always recognize it in our encounters — does it come all from within, or does it require some tacit persuasion?

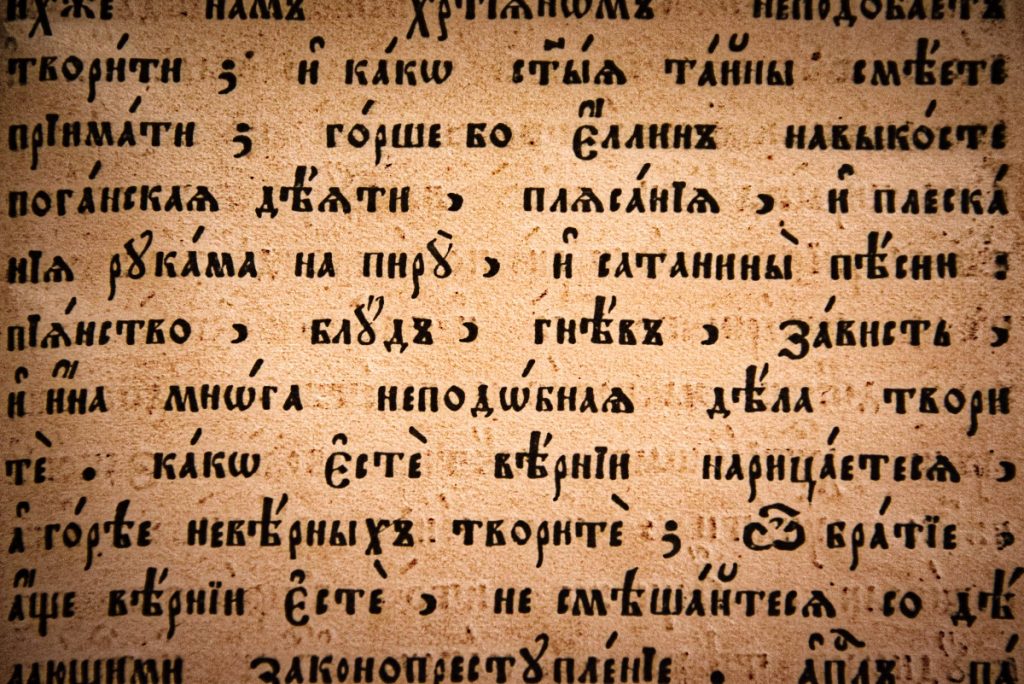

CHURCH SLAVONIC

Nastia and i were now loosely retracing my cycles from two years before along the Danube Delta and the Black Sea shore — should we go to Vylkove or not?

The town of Vylkove, known as the Ukrainian Venice, is (to my cool long-term traveling attitude) a depressingly touristic place — you can’t go for longer than five minutes without having a teenager on a scooter ride by to interrupt whatever you’re doing and ask if you want a boat tour. They’ll take any opportunity — if you ask one of them for directions, they might pitch you a boat tour — i pictured myself falling off my bicycle, or whatever, only to have one of them approach and ask, “Hey, is everything alright? — you don’t seem very happy — looks like you could use a boat tour!”

Nastia and i had both been there already, and we didn’t care much to return — except that Vylkove is where we were told we would find Lipovans, of whose existence i was oblivious just a week or two before. After a few confusing leads from a scooter boy, what i judged to be a resentful former member of the community, the alcoholic he took us to, and two teenage girls whom i’d approached then thinking they might as well be the most reliable source of information around, an old lady who’d been observing some of that play out from across the street invited us inside — we soon found ourselves drinking sparkling water and eating something i don’t remember in what turned out to be the communal area behind the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin.

When they read Nikon on my camera, they pointed at it and smiled — that’s the name of the patriarch who, in the 1600s, introduced the ecclesiastical reforms the Old Believers would oppose and resist. A period of persecutions began, and many of them fled Russia — some of them resettled along the Prut River and on the Danube Delta in what’s become the border region between present-day Moldova, Romania, and Ukraine, and came to be known as the Lipovans.

The origins of the denomination are uncertain, and legends abound — my favorite one was that, while they were on the run, they would hide in linden trees (in Russian, липа – lipa). They’re also known for a number of superficially small but nevertheless important distinctions in their rituals and symbols — it made unique sense to me that they bury their believers with a cross planted at their feet, not the head — “it will be handier when we get up from the grave on the day of our resurrection.”

The Lipovans speak Russian in their everyday lives, but their liturgy, prayers, and religious texts and instruction, in general, remain untranslated from the language they spoke nearly 400 years ago when the schism broke out.

SURZHYK

Some of you who’ve been following me since 2017 might remember Uncle Goge and Aunt Luda — i learned on this tour that that’s how one may affectionately and respectfully refer to adults in the Ukrainian countryside.

I could communicate with them substantially better this time around, and was unsure if some of what i didn’t understand was just their local strand of Ukrainian, or influences from Russian — “what language do you speak with each other?” — They answered casually, “Ukrainian, or Russian — well, Surzhyk.”

Surzhyk, a Ukrainian word for flour made from a mixture of grains, or the bread made from such flour, denotes the vast spectrum of sociolects of Russian and Ukrainian in which about 5 million people in Ukraine and adjacent areas communicate — whether one is talking about Ukrainians who have historically Russified their speech to communicate with authorities or Russian-speaking Ukrainians (such as the clerk i interacted with at the post office last week) who’ve adapted to the recently affirmed public status of the state language, the number of people formally speaking neither Ukrainian nor Russian is bound to increase.

I saw it fitting to place myself in this last photo, with which i conclude this note by insinuating what i enjoy the most — watermelons (Goge doesn’t use nitrates either) — and, of course, some degree of conceptual deconstruction.

I want to clarify that the idea of this essay is not to highlight the predominant local language in each district, but rather illustrate the diversity of what people speak at home across the whole region. We wound up meeting (and documenting) enough representatives that, with some patience and a little creativity, it was possible to select a unique one from each of the nine districts of Odesa comprising Southern Bessarabia. I also wanted to show that, while Albanians, Bulgarians, Gagauzes, and Moldovans — who are (still) present in large enough numbers and somewhat organized in local communities — might offer the most notable and easy to find examples of this cultural variety, it doesn’t end there.

“The state language of Ukraine is the Ukrainian language,” declares Article 10 of the Constitution — it then adds

The next two lines in Article 10 say that, “[i]n Ukraine, the free development, use and protection of Russian, and other languages of national minorities of Ukraine, is guaranteed,” and that “[t]he State promotes the learning of languages of international communication.”

While the law doesn’t restrict language usage in private communication, it seems to discourage the dissemination of Ukrainian content in languages that are used by significant proportions of Ukrainians — particularly in Russian. Article 24 of the bill stipulates that 90% (80% for local broadcasters) of daytime and early evening radio and television broadcasts must be in Ukrainian. Article 25 implicitly excludes Russian from the list of languages in which print media may be published without a corresponding version in Ukrainian, while wittily allowing that to be done in indigenous languages, English, as well as any official language of the European Union [2, 3].

Interestingly, the president who pushed for and signed the legislation just before the end of his term is from the region — Poroshenko grew up in Bolhrad [4, 5].

The extent to which the law will be enforced, what exceptions might be granted by further legislation, and their long-term effects on Ukrainian society remain to be seen.

What do i care anyway? — don’t i come here from the outside? — does it make a difference whether i have to learn Ukrainian or Russian? Indeed, i don’t have to learn either, and i’m quite eager to learn both, and eventually be able to communicate with Ukrainians in whatever language they prefer — that’s how privileged i am.

Many Ukrainians can’t say the same.

I’ll wrap up with a few questions that came to me as i traveled through the region, talked to some of their residents, learned about the law, and worried about the future.

Russian was reported to be their first language by 29% of respondents in a 2012 countrywide poll by RATING — a more recent survey from 2015 found that 78% of the residents of the city of Odesa who are eligible to vote speak the foreign language at home — the official language of the defunct Soviet Union is still widely used as the language of interethnic communication in its former territories, especially among people who grew up in the Union and are now 40–50+ years old. Might the law make it too onerous to produce and disseminate content of Ukrainian interest in Russian? If so, where will Ukrainians who feel more comfortable in that language turn to for their news and entertainment? One can already see parabolic dishes in many (if not most) homes throughout the Odesa region — some (if not all) of them are already tuned to Russian channels — is that the kind of thing the legislators wanted to avoid?

Does it matter what language(s) people speak? — does that matter more than whether or not they understand each other? Is forcefully pushing the Ukrainian language across the country a fruitful narrative to pursue? — will that bring Ukrainians together or further divide them? — are there other strategies to affirm Ukrainian as the language of interethnic communication? — could the transition at least be smoother?

Denmark, which is repeatedly ranked among the top happiest nations and best functioning democracies on Earth, is a remarkably homogeneous country. Is diversity beneficial or detrimental to our individual and collective wellbeing? — does it even matter? — should we value it at all? Can a stable national identity be constructed without suppressing cultural differences? — can democracy work in a vast and pluralist society?

Whatever the answers to these questions, it’s increasingly clear that we’re quite far from the end of History. And Ukraine seems to be one of the best seats from where to watch its next act unfold.

___

Featured photo: outline of our route through the administrative region of Odesa (courtesy of plotaroute.com and © OpenStreetMap contributors)

Sign up for my newsletter and receive long-term travel

inspiration & advice delivered weekly, straight into your inbox